For many years we cooked a Christmas Eve spread for around 25 family members. Since we have only our own palates to please this year, we decided to make the holidays festive by beginning a marathon of cooking dishes often associated with good times and holiday cheer, at least in Mexican and Latinx households. We’re talking about tamales and moles (MOH-lays, in case you were wondering how to pronounce it). This will be the beginning of a series with recipes for our versions of the seven classic moles of Oaxaca and some ways to serve them.

Why Oaxaca? Mexico has a rich variety of regional cuisines, but we think of Oaxaca as the mother kitchen for them all. The Isthmus of Tehuantepec was the spice road and the cultural mixing pot of pre-contact Mesoamerica with Central and South America. Farmers here domesticated corn, tomatoes, tomatillos, and chile peppers and traded them far and wide for such commodities as quetzal feathers, cacao, and possibly coca. The Spaniards brought saffron, apples, and chickens. As the richest and most complex of Mexican cooking styles, Oaxacan cuisine plays a role similar to New Orleans cuisine in American cooking—a rich gumbo of many inspirations.

Some notes about moles

The building blocks of Oaxacan cooking are the mole sauces. There are seven classics and as many variations of them as there are cooks. The simplest—like rojo, verde, and amarillo—are light and bright. The most complex—manchamanteles, negro, and the stew-like chichilo—are heady and rich. Some are thickened with bread crumbs or tortilla dough (masa), others with nuts and seeds.

Say ‶mole″ to most American diners and they immediately think of mole poblano, or the ‶mole of Puebla.″ Its three principal flavors of hot chile peppers, rounded chocolate, and a distinct sweetness is a big hit all over North America. The signature mole of Oaxaca is similar but it is darker, less sweet, and more complex. It’s properly called mole negro, or ‶black mole.″ We’ll get to it in the dark and cold month of January, when it is a perfect antidote to the blustery ice and snow of a New England winter.

One of the distinctive characteristics of classic mole sauces is the basic paste is pan-fried in a little bit of hot fat. We suspect that this cooking method came about because the boiling point of water is so low at high altitudes that only hot fat could thoroughly cook the paste that would eventually be thinned out to make the sauce. It doesn’t take much. Home-rendered lard is traditional; some cooks use chicken fat skimmed from making chicken stock. Vegetable oil also works, of course, but it’s best to mix in a little toasted sesame or peanut oil for character.

MOLE ROJO (RED MOLE)

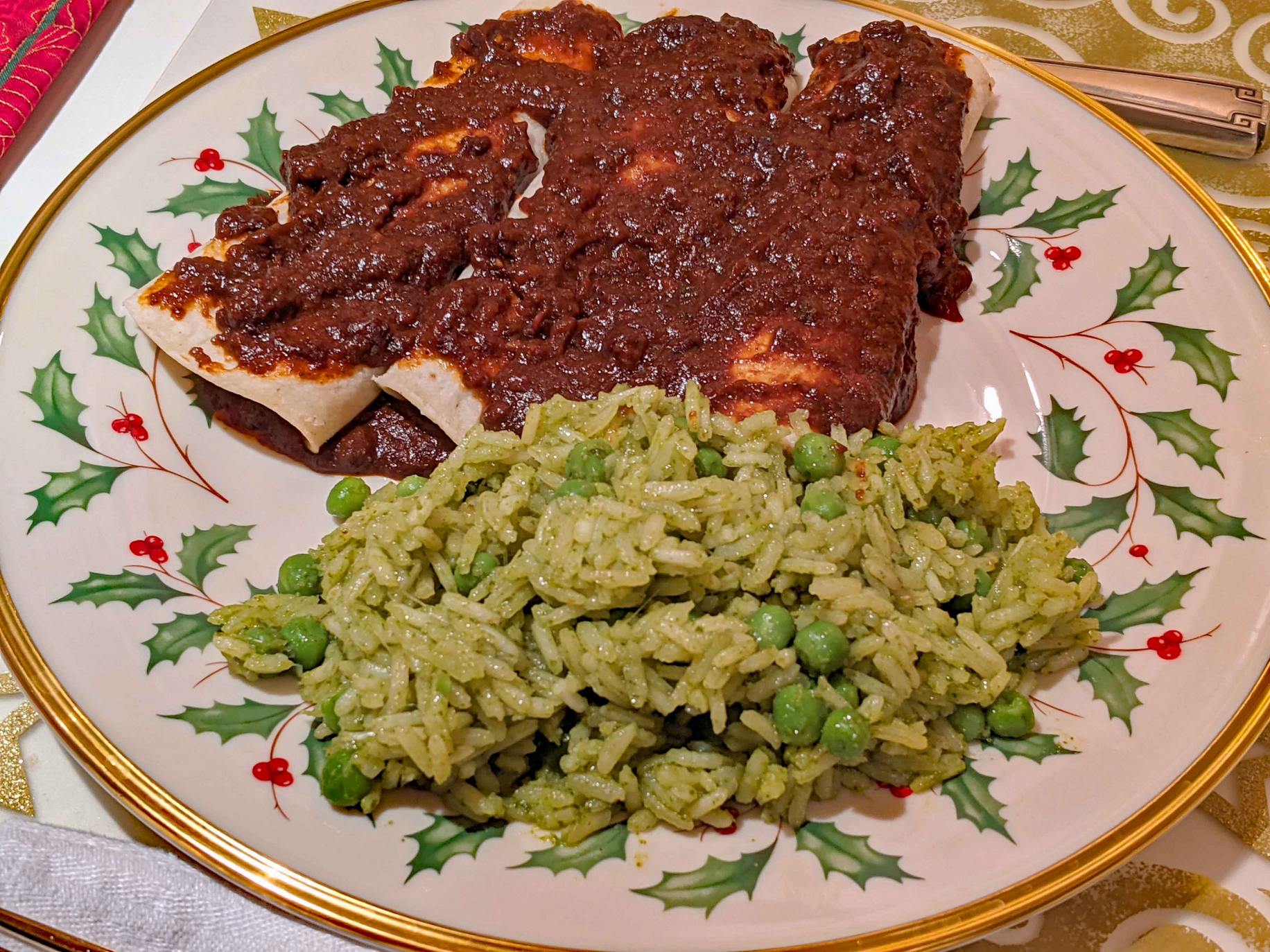

We decided to start with mole rojo because it’s easy to make. It is the simplest of moles but there are hundreds of variations. We base ours on Zarela Martinez’s recipe in The Food and Life of Oaxaca. We like to serve it over chicken enchiladas and—¡Feliz Navidad!—with green rice. For that dish, we use Rick Bayless’s Mexican Kitchen recipe, conveniently republished online by NPR.

4 large ancho chiles, stems and seeds removed

6 large unpeeled garlic cloves

1 large very ripe tomato (3-4 hothouse cocktail tomatoes suffice in winter)

1 onion, peeled and cut in quarters

1-inch stick of Mexican cinnamon (canela)

1/4 teaspoon black peppercorns

8 whole cloves

1 teaspoon dried Mexican oregano

1/2 teaspoon dried thyme leaves

2 bay leaves

12 ounces chicken stock (preferably homemade)

3 tablespoons chicken fat (skimmed from homemade stock) or vegetable oil

1 cup of fine crumbs made from stale bread (about 4 ounces bread)

1 teaspoon salt (possibly more to taste)

2 teaspoons sugar (possibly more to taste)

DIRECTIONS

Place chiles in heatproof bowl and cover with boiling water. Let steep at least 20 minutes.

Roast garlic cloves on a hot griddle, turning frequently so they don’t burn but cook through. When cool, peel and reserve.

Add tomato and onion to a small pan of boiling water and cook for 10 minutes. Remove vegetables and set aside a half cup of boiling liquid. When vegetables cool slightly, remove tomato skins and place vegetables with roasted garlic and reserved water into a blender. Blend until smooth and strain through a coarse strainer into a bowl. Set aside.

Grind the cinnamon, peppercorns, cloves, oregano, thyme and bay leaves in a spice grinder. Set aside.

Drain the chiles and place in blender jar with the stock. Process until smooth, pausing to scrape down the sides of the blender jar. (We use an immersion blender in a wide-mouth quart canning jar.) Strain the blended chiles through a coarse sieve or strainer into a bowl. Use a wooden spoon or silicon spatula to press through the mesh, discarding the seeds and pulp left behind. Combine with the tomato purée.

Heat the chicken fat or oil over medium heat in a Dutch oven until it ripples. (The high sides keep the sauce from spattering everywhere.) Add the spices and cook for about 2 minutes, stirring often. You want to toast the spices—not burn them. Stir in the chile-tomato mixture. Cover and cook 10 minutes, taking off the cover occasionally to scrape the bottom and stir. Add breadcrumbs and salt and cook, stirring constantly, for 2-3 minutes. If the sauce seems too thick, thin with a little water. Stir in sugar, mixing well. Taste for seasoning, adding more salt and sugar to taste.

Serve over enchiladas with a side dish of green rice.