We’ve always had a soft spot for Spanish tiles. Ever since our first visit to Madrid’s decorative arts museum, our Platonic ideal of a kitchen has been the museum’s 18th century tiled kitchen from Valencia. That was until we came to spend some extended time in Valencia.

Many parts of Spain have ceramic traditions, some dating back to Roman Hispania. (Sevilla sisters Justa and Rufina were martyred in the 2nd century for refusing to make ceramics for a pagan festival.) The Moors brought their own pottery traditions with them and the Spaniards kept soaking up the influences like sponges. The Valencia region—especially the village of Manises—reached its ceramic apogee in the 17th–20th centuries. Now a neighborhood of Valencia on the airport Metro line, Manises still makes ceramics. They decorate the facades of houses and businesses all over town. The Mercadona grocery store in the former municipal market is covered with painted ceramic scenes.

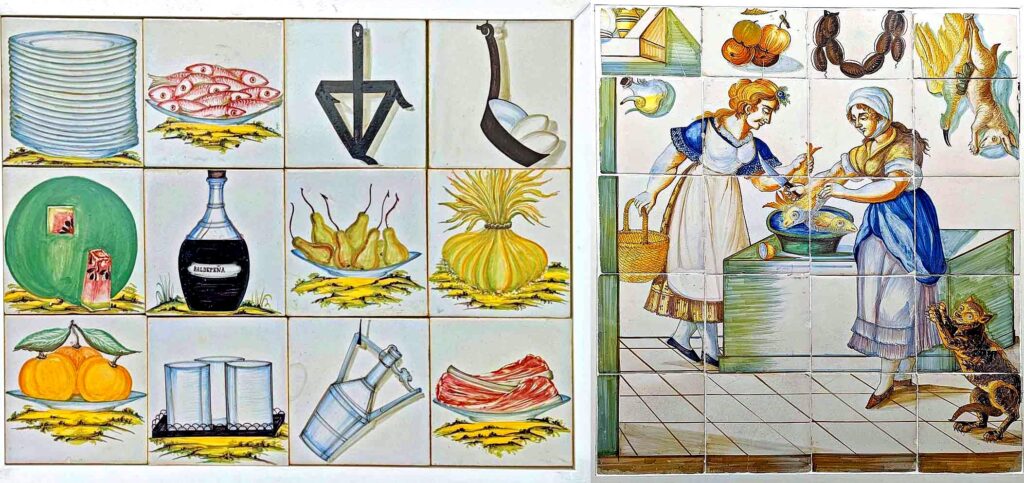

To get a real taste of the depth and breadth of the ceramic tradition in Manises, we visited the Manises Municipal Ceramics Museum (c/ Sagrari 22, Manises; 961 521 044; comunitatvalenciana.com/en/valencia/manises/museums/municipal-ceramics-museum; free). Its collection of more than 5,000 pieces provides an overview of the village’s production from the 14th century to the present. The kitchen scene at the top of this post faces the entry desk. The tile panels shown below are in one of the upstairs galleries. We’re particularly taken with the cat clawing at its mistress’s dress while the woman prepares fish.

Peeking into Valencian kitchens of different classes

The kitchen as an expression of wealth and status long predates Viking ranges and SubZero refrigerators. But we were also curious how the non-royals cooked. (Okay, the nobility didn’t actually make their own meals, but you catch our drift.) In our quest to visit lesser known museums that wouldn’t have crowds, we discovered the singer and actress known professionally as Conchita Piquer. She had a grand career that began with singing on Broadway while still a teenager and continued into the 1950s as she toured Spain and Latin America. She even married a bullfighter.

But the House Museum Concha Piquer (c/ Ruaya 23; 963 485 658; valencia.es/-/infociutat-casa-museu-concha-piquer; free) occupies a modest building at the edge of the old city. She was born here in 1906 and grew up here—until she started her career. While some rooms are devoted to photos and memorabilia of her career, the upper level shows the family living quarters. They were, to say the least, cramped. Smallest of all seems to be the minuscule kitchen (at right) with its tiny two-burner cast iron stove and stone block sink.

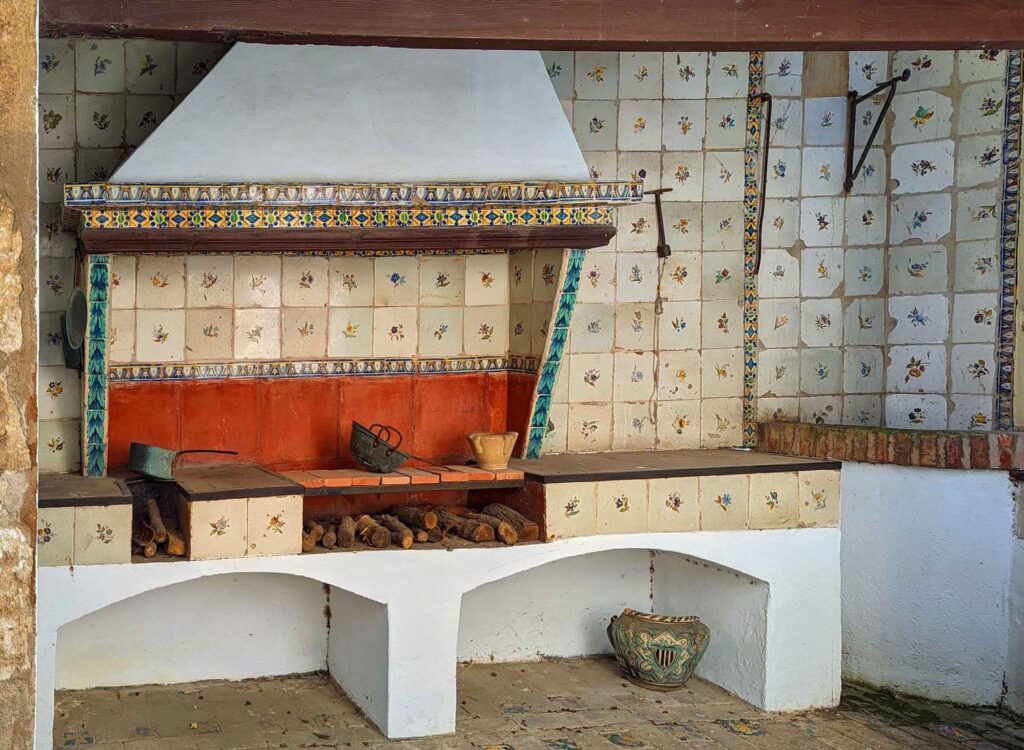

By contrast the House Museum Benlliure (c/ Blanquerías; 963 919 103; valencia.es/-/infociutat-casa-museu-benlliure; free) shows the upper middle class comforts enjoyed by painters José Benlliure Gil and his son José Benlliure Ortiz. We didn’t see the original indoor kitchen. We’re guessing it’s part of the museum’s office space. But a sumptuous garden separates the house and the studio building. One side near the studio is devoted to a lovely outdoor kitchen, shown below. You could make a lot of meals here without heating up the house. Note that it’s all tiled.

Ceramics museum boasts the ultimate tiled kitchen

Some of the best tilework in Valencia is found at the González Marti National Museum of Ceramics (c/ Poeta Querol 2; 963 516 392; culturaydeporte.gob.es/mnceramica/en/home.html; €3) The piece de resistance is the reconstructed Valencian kitchen decorated with borders made with 18th and 19th century tiles. Panels set into the walls depict scenes of daily life along with religious subjects. Bowls and plates and pitchers and other decorated ceramics of the same era sit on the counters. Here’s a short video that pans from left to right.