You’d have to be living under a rock not to know that vermouth (or vermut) is having a moment, both in Spain and the U.S. Our own history with fortified wine muddled with botanicals and aged in a barrel goes back a few decades when Lillet was still hip in certain suburban settings. We were quite taken with the ice-cold, slightly sweet and bitter aperitif when the late, great mystery and suspense writer Andrew Coburn poured us some on his back deck one evening. He’d picked up the habit on the French set of Un dimanche de flic, a film adaptation of his novel, Off Duty.

Lillet is not vermouth, but they are kissing cousins. In today’s vermouth fever, almost any aromatized wine passes muster as vermouth, a legacy of the decades-long ban on wormwood. (Without wormwood, vermouth was just another aromatized wine.) Lillet, for example, derived its bitterness from quinine and bitter orange.

Hey, we’re not purists. Part of the appeal of vermouth is that anybody who can make gin can make vermouth. The concept is similar—flavor the product with your own bill of botanicals. If you use flavors from a narrow vicinity, you have a “local” vermouth or gin. It opens up a world of interesting flavors.

We have puckered our way through glasses of house vermut in Spanish tabernas. Mostly they’re great for breaking up a chest cold in the winter, but we’d rather drink table wine when not infirm. California producer T.W. Hollister (https://twhollister.co/), though, may have changed our minds about vermouth with a local flavor profile.

California dreaming

You can read all the history on the company website. Suffice it to say that Hollister produces “vermouth from Gaviota, California.” That’s a pretty local ID. Moreover, the process uses a lot of botanicals harvested from the family spread. It makes sense, given that an ancestor created a veritable arboretum/herbarium of species from around the world. Hollister makes both dry vermouth (often called “French vermouth”) and a sweeter red vermouth (often called “Italian vermouth”). They are both branded “Oso de Oro,” or Golden Bear. It’s a California thing.

You can read all the history on the company website. Suffice it to say that Hollister produces “vermouth from Gaviota, California.” That’s a pretty local ID. Moreover, the process uses a lot of botanicals harvested from the family spread. It makes sense, given that an ancestor created a veritable arboretum/herbarium of species from around the world. Hollister makes both dry vermouth (often called “French vermouth”) and a sweeter red vermouth (often called “Italian vermouth”). They are both branded “Oso de Oro,” or Golden Bear. It’s a California thing.

The dry vermouth is the simpler of the two, as it’s macerated with a dozen botanicals. The ones that come forward in a sip over ice are orange peel, rosehip, and the vaguely medicinal flavor of hyssop. The bitter edge at the back is the wormwood, and it gives a backbone to the the dry apéritif.

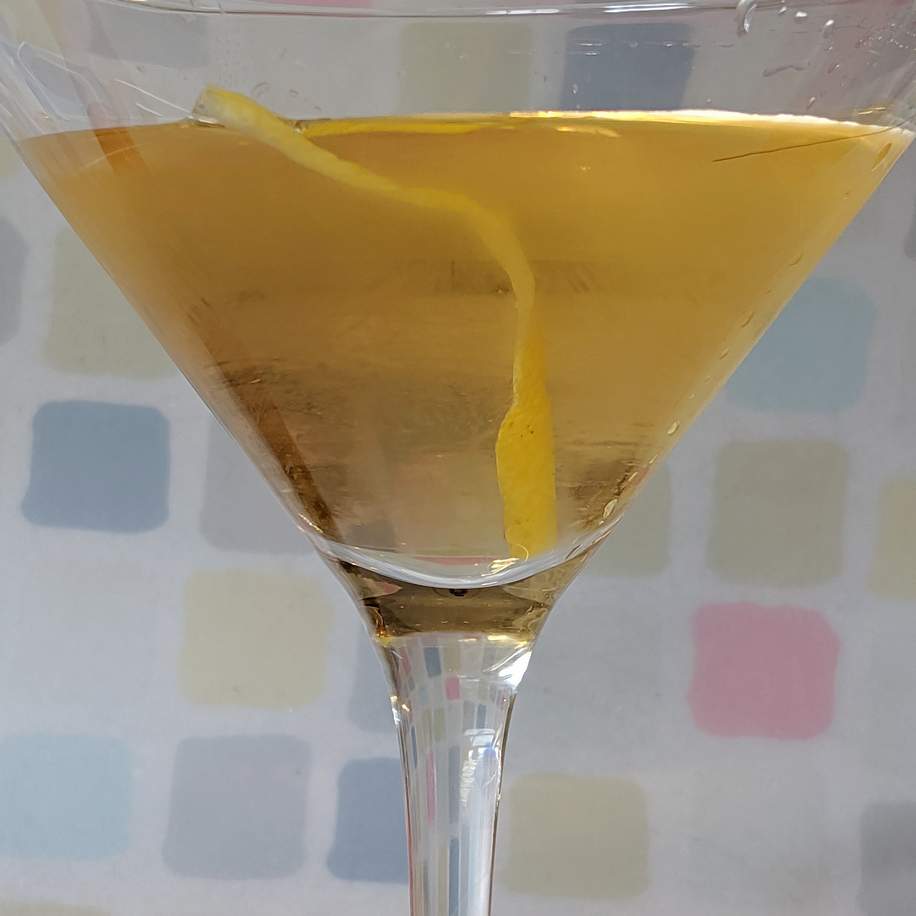

Oso de Oro dry vermouth really shines, however in a martini. Following George Yatchisin’s suggestion in last spring’s Edible Santa Barbara, we inverted the classic proportions. We added 5 ounces of vermouth to 2.5 ounces of gin (we used Jawbox from Belfast, Northern Ireland), shook with ice and strained into a glass with a twist of lemon. Brisk, floral, and refreshing, the drink was a winner.

Gaviota takes Manhattan

Oso de Oro red vermouth shows a family resemblance, but it’s far more complex than its dry sibling. The base is a white wine, and the main color comes from adding caramel at the end. The citrus flavors of grapefruit and blood orange are quite pronounced. Ginger gives it some heat. Hummingbird sage (a California native) provides a sharp herbal note that keeps the drink from being cloying. Of course, a bit of wormwood on the back provides some bite.

Oso de Oro red vermouth shows a family resemblance, but it’s far more complex than its dry sibling. The base is a white wine, and the main color comes from adding caramel at the end. The citrus flavors of grapefruit and blood orange are quite pronounced. Ginger gives it some heat. Hummingbird sage (a California native) provides a sharp herbal note that keeps the drink from being cloying. Of course, a bit of wormwood on the back provides some bite.

The red vermouth is a splendid sipper, but it also makes an excellent Manhattan. Again, we inverted proportions (5 ounces red vermouth, 2.5 ounces whiskey), added two dashes of bitters and a homemade Benedictine cherry. We made the fruit by simmering a dozen pitted cherries in 3 tablespoons simple syrup and 1 tablespoon lemon juice with a stick of cinnamon and a pinch of nutmeg. After removing from the heat, we added 1/3 cup of Benedictine, let cool, and bottled. Refrigerated, the cherries keep as long as it takes to make 12 Manhattans. It’s a race to see which empties first—the vermouth bottle or the jar of cherries.