Greek traders brought wine grapes to Istria roughly 2,900 years ago, yet quality modern winemaking in the area didn’t really start until after the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991. Politics always seemed to get in the way of making premium wines in this crossroads region on the northeast coast of the Adriatic.

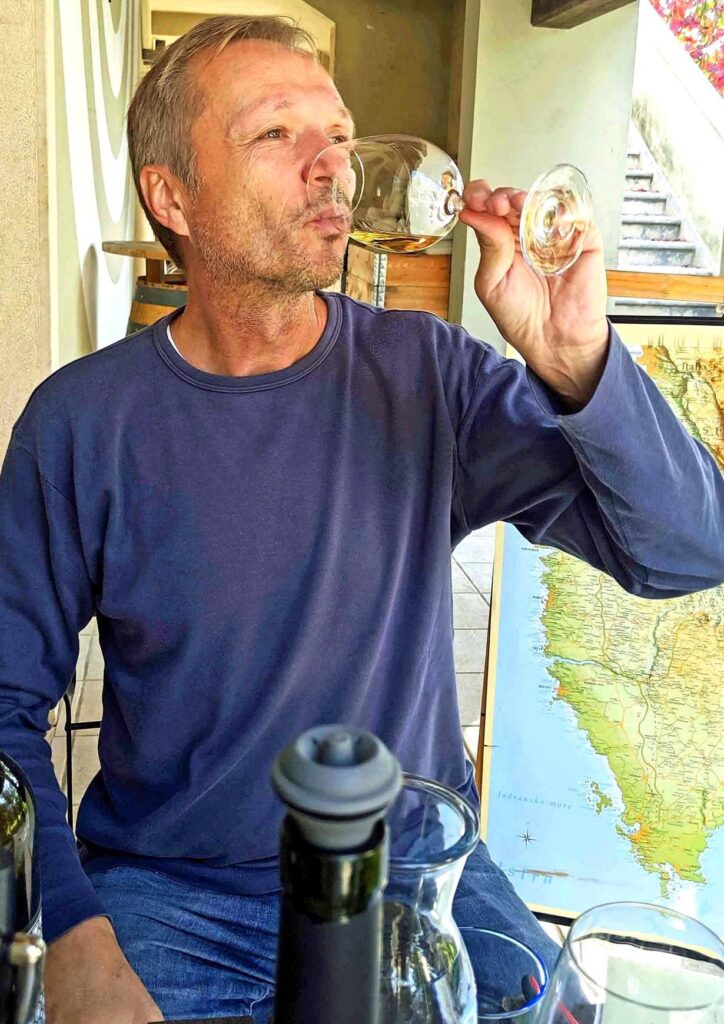

‶My grandfather was born in Austria,″ pioneer winemaker Ivica Matošević (pronounced ee VEET sa – ma TOE she vitch) told us. ‶My father was born in Italy and I was born in Yugoslavia. My children were born in Croatia.″ He pauses for effect. ‶And the family has never moved.″

Matošević is one of a handful of visionaries who put Istria on the viticultural map in the 1990s, releasing his first imitation of a Beaujolais Nouveau in 1996 and getting serious about fine wines a few years later. By his own account, he began as a hobbyist. While he was studying for a doctorate at the University of Udine in nearby Italy, Italian wine culture captivated him. In the early 2000s, he began planting vineyards near Buje in northwest Istria and later in Grimalda in central Istria. Today, Vina Matošević produces about 100,000 bottles a year, making it one of Istria’s largest producers of premium wines.

The wine cellar and tasting room are located in Matošević’s home village of Krunčići, south of Buje and a short drive inland from the resort village of Rovinj. It’s open daily May-October, closed Sundays and holidays the rest of the year. We should have reserved, but when we stopped by unannounced, one of the staff was happy to give us a tasting. Before long, Ivica Matošević himself joined us.

Getting a proper introduction to Istrian wine

Affable and fully fluent in English (in addition to the usual basket of languages spoken in Istria), Matošević gave us a quick primer about Istrian wines. The two principal indigenous grapes are the tannic red Teran and the briskly aromatic white Malvazija Istarska. But since the launch of premium winemaking at the turn of the century, many vineyard owners have also planted grapes more often associated with Italy and France. Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Gamay, Refosco, Barbera, Pinot Noir, and Syrah are the main red varieties. The whites include Pinot Grigio, Pinot Bianco, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon Blanc.

Istrian vineyards have two dominant soil types, which Matošević calls ‶red earth″ and ‶white earth.″ Both are clay-based, with more broken limestone in the white soil and more iron and other minerals in the red soil. The bulk of the Teran vineyards as well as his international grapes are planted in red soil in central Istria near Grimalda. The white earth of northwest Istria near Buje is home to the main vineyards of Malvazija Istarska.The flagship wines of Vina Matošević, in fact, are called ‶Alba″ after the Italian and Spanish word for ‶white.″

One geeky footnote about Istria’s leading white: Malvazija Istarska is unrelated to any of the Malvasia varieties that originally came from Greece. The Tuscan variety called Malvasia and Croatian Malvasia grown near Dubrovnik align more closely with spicy Muscat. The Istrian grape typically shows peach and apple flavors with hints of lime or green grass—a far less honeyed style.

The many faces of Malvazija at Vina Matošević

Sixty percent of the production at Vina Matošević consists of Malvazija, and the biggest selling wine is the simple Alba. Picked in late summer from several different vineyards in Buje, it is fermented without skin contact and allowed to sit on its lees until January. The winery blends the different vats in March and releases bottles around June 1. By late October, when we tasted the previous year’s vintage, it was developing some nice herbal and floral notes to augment the basic minerality. Characteristic of the grape, it was also showing a slight aftertaste of bitter almonds. After our visit, we made a point of ordering this wine for dinner at Rovinj’s seaside fish restaurants.

Matošević makes three other variations of Malvazija Istarska. One is aged briefly in French oak, then finished in stainless steel. Production is small, perhaps because the winemaker seems to prefer aging the wine in acacia, a wood native to Croatia. The mild wood doesn’t overpower the wine like oak. It also gives a hint of smokiness (some tasters describe it as ‶bacon″) and definitely prolongs the length of time the wine keeps in the bottle.

The true premium version of Malvazija Istarska is called Alba Antiqua. Made from grapes from a single vineyard near the Istrian village of Krasica, this wine is fermented on the skins and aged on the lees in French oak and acacia barrels for 30 months before bottling. It develops a deep color that resembles a mild honey. The aromas are earthier than the other Albas, the color substantially deeper, and the bitter almond aftertaste more pronounced. It’s a powerful white that pairs well with meats and heartier foods. Ivica Matošević also calls it ‶a wine for meditation.″ Not bad for a bottle that sells at the tasting room around $17.

Vina Matošević Wine Cellar & Tasting Room, Krunčići Krunčići 2, 52448 Sv. Lovreč, Croatia; +385 52 448 558; matosevic.com. Tasting of three wines is about $7.