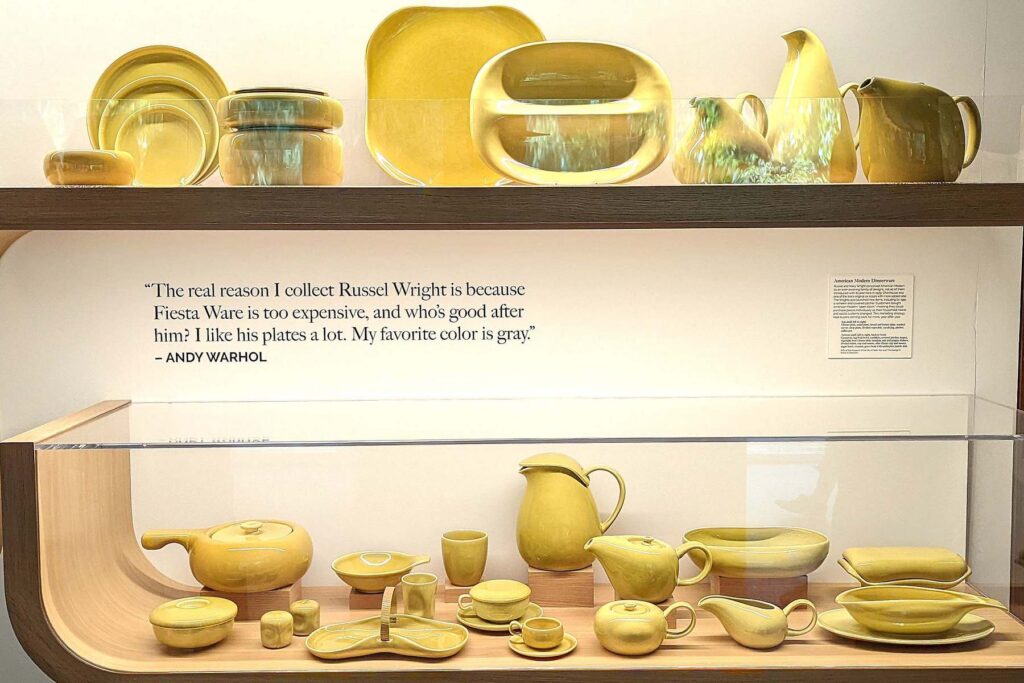

Regular followers of HungryTravelers might have noticed that most of the food we present is served on the same set of dishes. Those of you who haunt flea markets and shops that traffic in collectibles might even recognize them. They’re all ‶Iroquois Casual China by Russel Wright,″ launched in 1946. The dinnerware was meant to make modern design accessible to the masses. A teacher or a cab driver could afford the dishes.

Decades later, so could freelance writers. Antiques malls and flea markets yielded our collection of Iroquois Casual in four colors: Sugar White, Charcoal, Oyster, and what we think is probably Chartreuse. True to the original advertising, they’ve proven surprisingly durable.

Wright has been a fixture in our home for years. When we learned that Manitoga, his home and studio in upstate New York, was open for tours, we figured we should have a look into the designer’s own dwelling. The house and studio is now owned by the non-profit Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center (584 NY-9D, Garrison, N.Y.; 845-424-3812, visitmanitoga.org).

Casual Modernism in the Hudson Valley woodlands

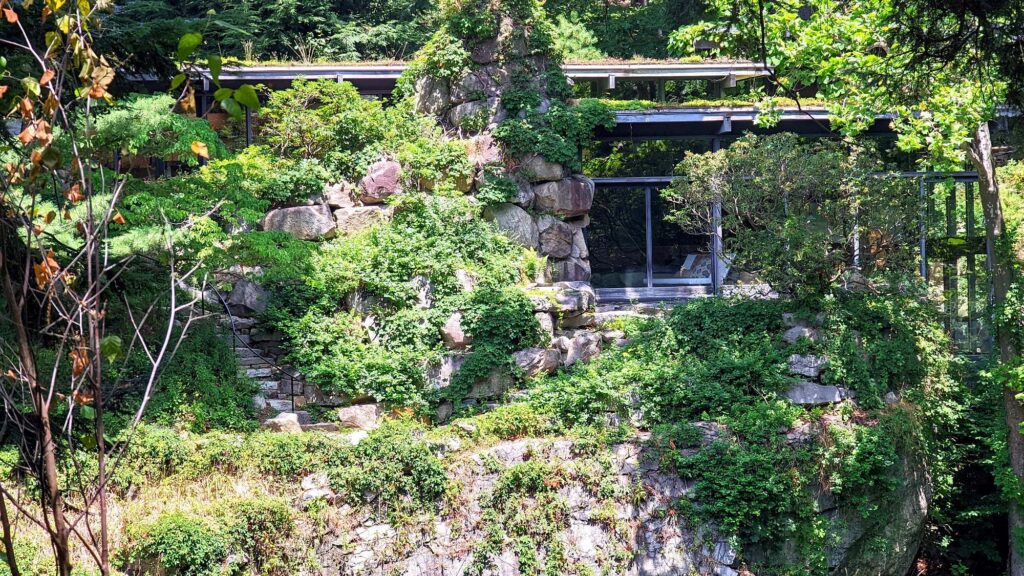

As an escape from Manhattan, Wright and his wife, Mary Einstein Wright, bought a former granite quarry in 1942 and set about transforming the 75-acre tract into a more naturalistic landscape. Our small group followed a guide along trails that the Wrights had cut and up stone steps that they had left deliberately uneven. We stopped to view the quarry that they converted into a pond. Finally, we caught a glimpse of the house and studio that were completed in 1961 (nine years after Mary’s death). It is wedged into a granite outcrop overlooking the pond and almost hidden in the lush natural growth. Even the roof is a thick pad of moss. The eco-sensitive, Japanese-influenced design was executed in conjunction with architect David Leavitt.

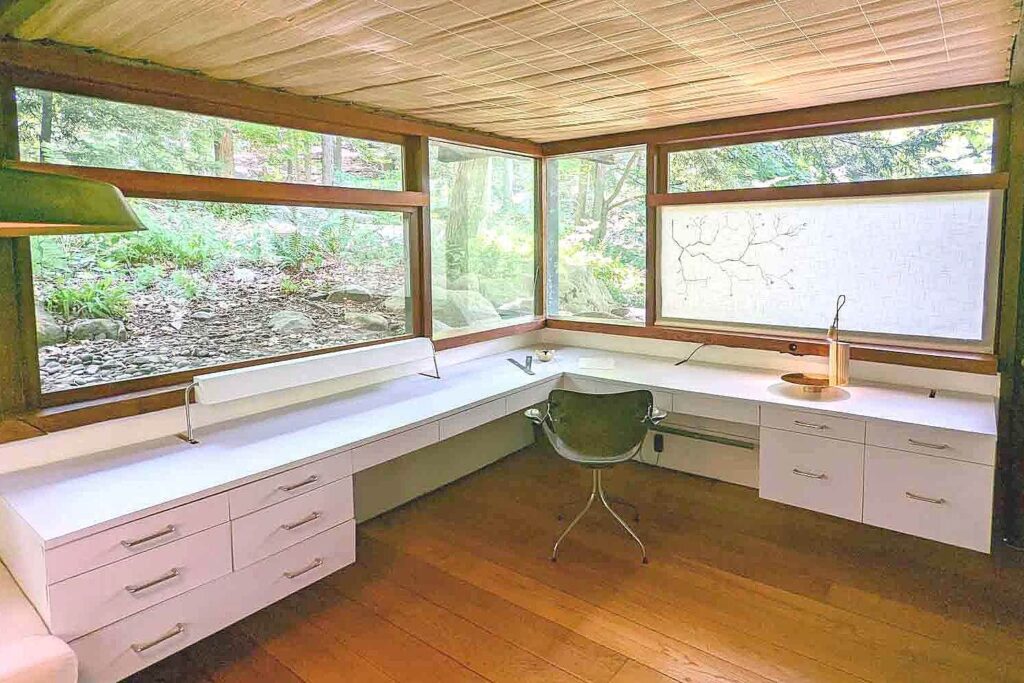

Wright’s designs were geared toward a relaxed, but still stylish way of life. In his own home, that aesthetic took the form of a big rock fireplace, a cedar log to help prop up the roof, and big wrap-around windows. Suffice it to say, that it bore no resemblance to our city condo in a 1920s apartment building constructed for factory workers.

But things looked more familiar when we descended a flight of stone steps to the kitchen and dining area. Wright’s casual living style had no place for a formal dining room. Instead, he placed a Saarinen tulip table adjacent to the kitchen where the shelves were filled with his dinnerware. He probably bought his table new — ours was a yard-sale find. It sits right outside our kitchen, in view of a cabinet filled with Casual Iroquois. We suspect Wright would approve.