My understanding of Chilean wine has been minimal. Exposed largely to inexpensive Cabernets and Sauvignon Blanc, I’ve long associated Chile with good bargains. Oh, the occasional eye-opening bottle of Carignan found its way to our table—and we rejoiced when one did and marveled at both the price—roughly six times the cost of a bargain Chilean red—and the great quality even at that price.

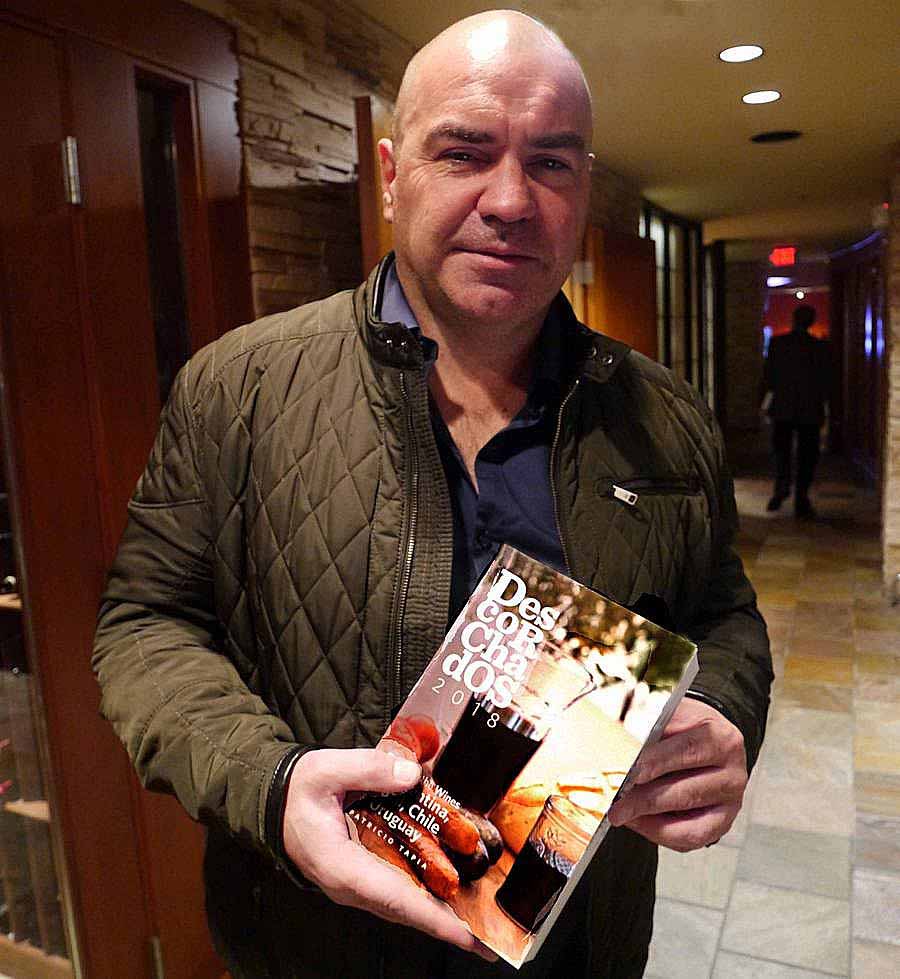

If the Wines of Chile marketing consortium has its way, we’ll all be having more of those aha! moments over glasses of Chilean wine. The group just barnstormed through Boston, Chicago, and D.C. with 15 wineries in tow for trade tastings of what they call “site specific artisan wines.” More important, they brought along one of the most genial and knowledgeable interpreters of the Chilean wine scene, critic Patricio Tapia (above).

Tapia led about thirty of us through a tasting of fourteen wines chosen to show the range of styles and grapes used in Chile, and some of the climatic extremes as well. A few basic points about Chile: The Humboldt Current keeps the entire coastal region cool, as the water flowing from the Antarctic rarely rises above 12°C (54°F). Coastal vineyards start the day bathed in cool fog, so they are the source for cool-climate Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, and Chardonnay. The second major point is that Chile tilts uphill going inland to the coastal range (10,000 feet). East of the coastal range, the land dips and then rises steeply again to the Andes (20,000 feet and up). In practice, this means that almost all vineyards are planted on slopes. Vineyards between the ranges often rely on irrigation, since they grow in rain shadows.

Surging interest in Chile’s oldest grape varietals

Tapia points out in his marvelous annual volume on South American wines, Descorchados, that the traditional low-alcohol country wine of Chilean farmers (pipeño) is almost always made from a grape called País in Chile. Recent genetic detective work has traced the varietal to the grapes introduced by the Spaniards to make sacramental wine. Extinct in Castilla due to the phylloxera infestation, it survives in the Canary Islands as Listán Prieto and has developed subvarietals known as Mission in California and as Criolla Chica in Argentina.

Tapia points out in his marvelous annual volume on South American wines, Descorchados, that the traditional low-alcohol country wine of Chilean farmers (pipeño) is almost always made from a grape called País in Chile. Recent genetic detective work has traced the varietal to the grapes introduced by the Spaniards to make sacramental wine. Extinct in Castilla due to the phylloxera infestation, it survives in the Canary Islands as Listán Prieto and has developed subvarietals known as Mission in California and as Criolla Chica in Argentina.

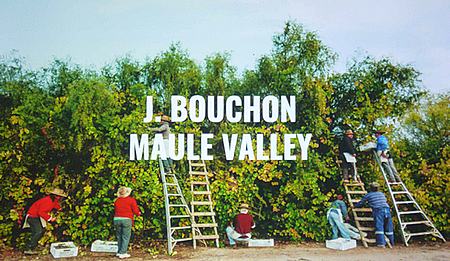

The grape actually grows wild in Maule Valley, where most cultivated plantings of País were ripped out a century ago to make way for Cabernet Sauvignon. In its wild state, as shown at right in a slide from the seminar, the vine climbs in messy tangle up to twenty feet high. Harvesting calls for ladders, as if the workers were picking tree fruit.

Serious winemakers have turned their attention to this heritage grape in the last two decades. J. Bouchon makes two versions—a soft and fruity País Salvaje from the unkempt wild vines, and a more Beaujolais-style País Viejo from bush-style vineyards more than a century old. Personally, I think of the wine from wild vines as a nostalgia project that honors Chile’s winemaking roots. My preference is for the bush-vine version.

Derek Mossman of Garage Wine Company (left) takes a more aggressive stance toward País. One of his recent bottlings is labeled “País 215 BC Ferment.” Rich in fruit but soft in tannins, it’s a pleasant wine for drinking with friends rather than for sipping in deep reflection. The “215 BC” reference is Mossman’s way of pointing out that Chile was making wine from this grape at least 215 years before the first recorded mention of the Cabernet Sauvignon grape.

Derek Mossman of Garage Wine Company (left) takes a more aggressive stance toward País. One of his recent bottlings is labeled “País 215 BC Ferment.” Rich in fruit but soft in tannins, it’s a pleasant wine for drinking with friends rather than for sipping in deep reflection. The “215 BC” reference is Mossman’s way of pointing out that Chile was making wine from this grape at least 215 years before the first recorded mention of the Cabernet Sauvignon grape.

From much the same area, Mossman, his wife Pilar Miranda, and Dr. Alvaro Peña also produce a rich and luscious Carignan from their Portezuelo vineyard. Production of Garage wines is fairly limited and most distribution in the U.S. goes to restaurants and wine bars. Ask for it by brand name.