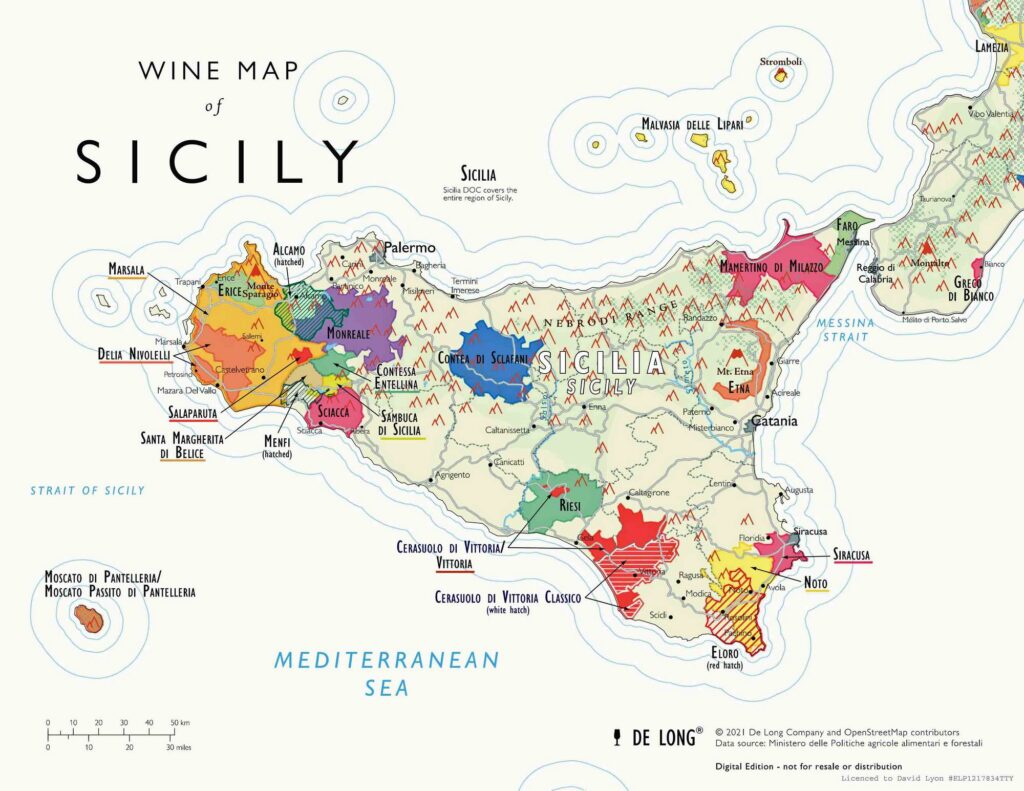

The continuing reorganization of Sicily’s wine regions, as reflected in the map above (courtesy of De Long), has brought considerable focus to what used to be a free-for-all. More than 60 varietals grow on the island, and more than two dozen are autochthonous — varieties that either originated in Sicily or have been grown here since the Phoenicians introduced advanced viticulture 3,000 years ago.

I had a chance to taste some modern twists on that grand tradition when Roberto Magnisi, production director of the Duca di Salaparuta group of wineries (duca.it/en), recently came to Boston. He brought outstanding wines from two of his company’s properties for a tasting luncheon at Contessa (contessaristorante.com). His group coalesced in 2001 when the Sicilian regional government sold Duca di Salaparuta to private investors. (It had passed into government hands during the land reforms that broke up the old feudal estates.)

Even under government control, Duca di Salaparuta had been a pioneer. In 1984, most Sicilian wineries were pumping out seas of bulk wine to sell elsewhere in Europe. But in that year, Duca di Salaparuta began restricting the yield of its central Sicily Nero d’Avola vineyards to produce some of the island’s first world-class reds with the Duca Enrico clone. It was a tipping point for Sicilian winemaking, inspiring a generation of small producers to craft quality table wines for the international market.

On the shoulders of a smoldering volcano

About two decades ago, the trade began to take notice of fine wines from vineyards on the slopes of Mount Etna, Sicily’s super volcano. Rich soils and a cool climate at high altitude (averaging 700m above sea level) produce extraordinary wines from Carricante (a white grape) and Nerello Mascalese (a red grape).

Our luncheon began with Lavico wines from the Vajasindi estate on the northeast flank of the volcano. We had an Etna DOC Bianco and an Etna DOC Rosso to accompany an avocado bruschetta with almonds, tomato, and basil and a thin tuna crudité with artichoke hearts and anchovy. The white was everything I like in a crisp white—almost bracing in its acidity with an intense fruit rather like ripe peach, The red was surprisingly complex, carrying a bit of spice in the mouth and just enough puckery red fruits to balance the anchovy.

A taste of relative antiquity

Magnisi chose the break between appetizer and main course to introduce Marsala from the famous Cantine Florio line. I confess that I never thought much about Marsala. The category was created in the late 18th century to satisfy the British love of fortified, oxidized, often sweet wines. It was the same era when Brits became a dominant force in the sherry and Madeira trades.

I had used cheap Marsalas to make the eponymous chicken and mushroom dish or to flavor zabaglione custard. But the Florio Marsalas were in a different league. As our interlude — almost as an aperitif — we tasted the 2009 DOC Marsala Vergine Riserva. Per DOC requirements, it had been fortified but not sweetened with concentrated must. The Florio was a grand example of a style — as sharp as a good fino, full of savory notes and a distinct saltiness. (Marsala cellars are seaside, and the salt air definitely influences the finished wine.)

Gauging young and old big reds

We switched back to unfortified wines for the main course plate, which included rigatoni with lobster Fra Diavolo sauce, a small black-pepper filet, and a Tuscan-style butter chicken breast. The salty, buttery chicken was a perfect pairing with the Marsala Vergine. The other two proteins went better with the examples of Duca di Salaparuta’s Duca Enrico, the company’s flagship red made from Nero d’Avola.

The 2018 was still a little unruly. Magnisi likened it to a young boy feeling his oats. The red fruit was a mixed bowl of strawberries, tart cherries, and raspberries. Spice and vanilla from the oak barrels had not quite married with all that fruit, but the wine was a good pairing with the beef filet. For simply pleasurable drinking, I preferred the 2004 Duca Enrico. Nearly two decades old, it still held a fruity freshness complemented by slightly acrid carob and licorice. Its age showed mainly in the softening of the tannins, which resulted in a distinct aftertaste and mouthfeel of chocolate.

Sweet touches at the end

But dessert also awaited — accompanied by Marsala, of course. The lighter of the two fortified and sweetened Marsala Semiseccos was from 2015, the heavier from 2001. Made from the same grapes, fortified and sweetened to the same levels, they demonstrated the distinct difference wrought by aging. The 2015 was imprinted with an angel’s share of 22%, indicating that it had lost that much volume as it aged in a combination of oak barriques and tuns. The angel’s share of the 2001 was 33%, resulting in a very intensely concentrated wine. I drank the 2015 with my cherry and pistachio tart, and saved the 2001 to savor (meditatively, as instructed) in lieu of coffee. It was a splendid introduction to the possibilities of Marsala. I’ll certainly think twice before wasting it on chicken or in custard.